Research

Animals learn from experience and flexibly adapt their behavior in a changing world

Our goal is to identify the neural computations that transform past experience into context-appropriate behavior—and to understand how these processes break down with aging and disease.

Research in the Heys Lab focuses on how brain circuits learn from experience and generate flexible, context-appropriate behavior. We ask how an animal’s learning curriculum and task structure shape the strategies it adopts, and how different circuits implement distinct learning algorithms to support those strategies. Together, these questions allow us to connect behavioral strategies to the neural dynamics and circuit mechanisms that give rise to them.

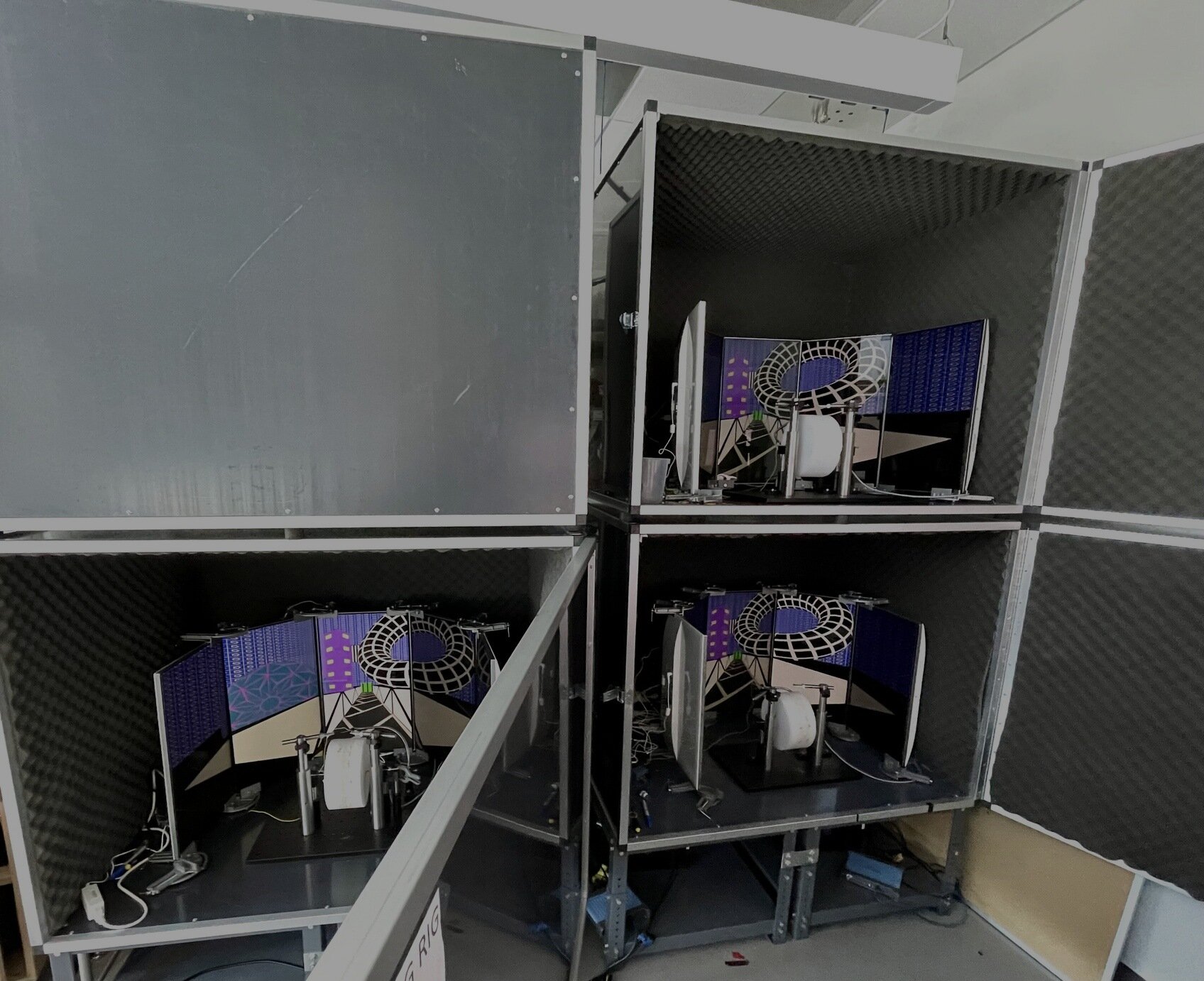

We study these problems using timing and naturalistic foraging tasks combined with large-scale neural recordings (two-photon calcium imaging, Neuropixels) and projection-specific manipulations, including closed-loop perturbations during behavior. Our experiments span both precisely controlled virtual-reality settings and freely moving environments.

We integrate these experiments with computational models: reinforcement-learning and normative frameworks that specify how animals should integrate temporal and spatial information, infer latent states, and form strategies; artificial neural networks and biophysically inspired cellular and circuit models that reveal the dynamics and representational geometry required to implement these computations. These models then inform targeted experiments, enabling direct tests of their predictions in vivo.

Temporal encoding in the brain

The events in the world unfold with rich and often predictable temporal structure. Animals have evolved the ability to learn these regularities, abstract them across contexts, and generalize them to guide behavior. Yet despite the ubiquity of temporal structure, we still have only a partial understanding of how neural circuits generate and use timing signals.

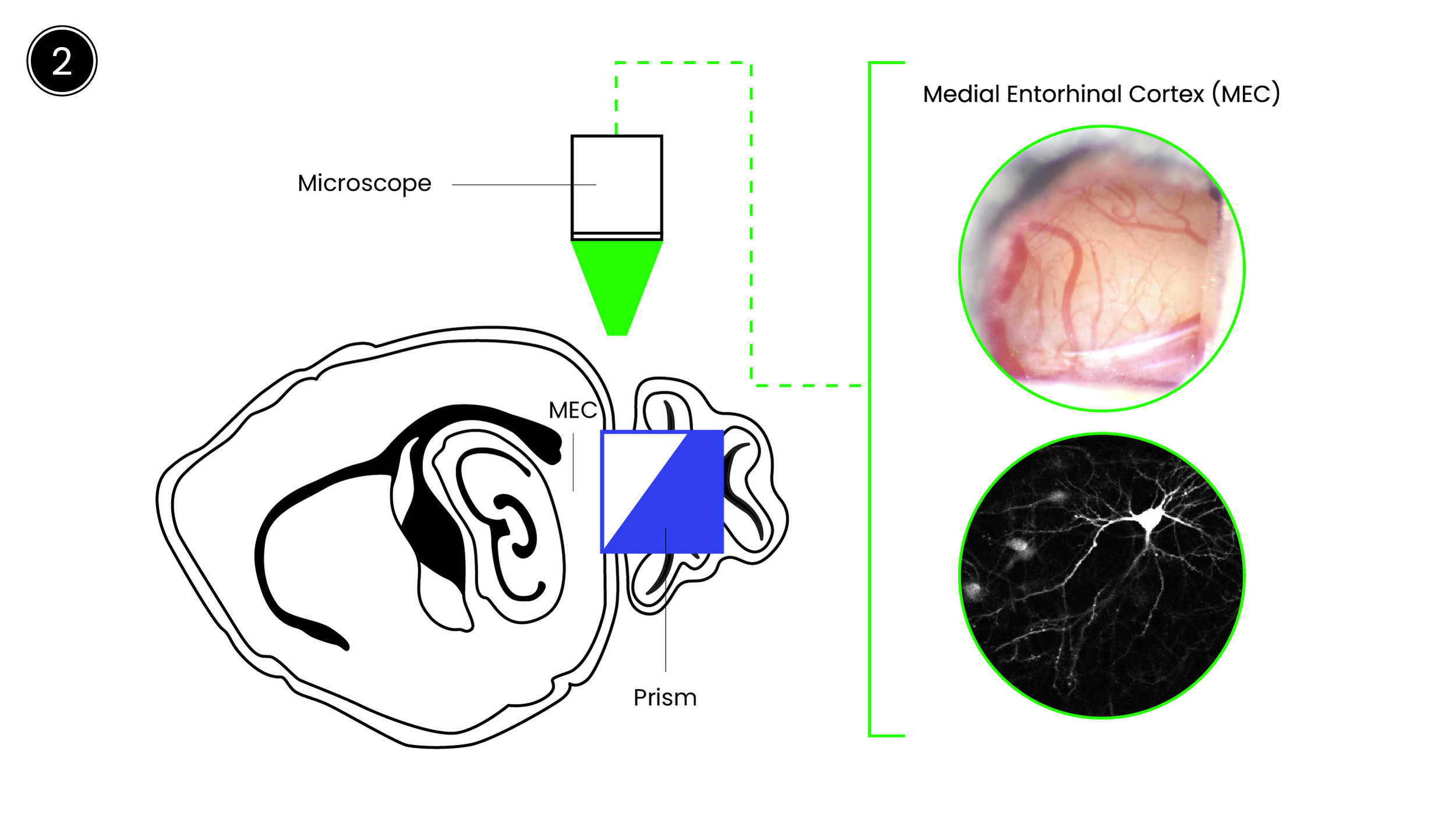

Our lab investigates how entorhinal–hippocampal circuits encode temporal information and how these signals support adaptive behavior. Work from our group and others shows that medial entorhinal cortex neurons generate “time cell” sequences that tile delays, with their structure shaped by behavioral context and task demands. We examine how these temporal codes arise, how learning experiences shape them, and how different circuits use them to solve ethologically relevant problems—such as predicting when rewards will occur, estimating when to leave a foraging patch, or linking events separated in time.

To address these questions, we use timing paradigms—including interval timing, odor–delay tasks, and foraging tasks with latent temporal structure—paired with large-scale neural recordings and projection-specific perturbations during behavior. Computational frameworks such as reinforcement learning, latent-state inference, and artificial neural network models provide complementary hypotheses about how circuits should generate and use temporal information.

How Learning Curricula Shape Adaptive Strategies Through Hippocampal–Entorhinal Circuits

In natural environments, animals rarely encounter tasks all at once—they acquire skills gradually, through structured sequences of experiences. This progression forms a learning curriculum, and it can shape which strategies animals adopt, the computations circuits rely on, and ultimately the neural dynamics that emerge during behavior. Understanding how curricula influence learning is essential for revealing why different circuits—or even different animals—arrive at distinct solutions to the same behavioral problem.

Our lab studies how training structure shapes neural representations and the strategies animals use across a range of temporally and spatially structured tasks, including odor-timing paradigms and naturalistic foraging with latent states. Work from our group shows that small changes in early training can produce large differences in both behavior and neural dynamics, suggesting that circuits may implement different learning algorithms depending on the path by which the task is acquired.

We approach these questions by training recurrent neural networks and animals under matched curricula. RNNs reveal how the same task can be solved using different dynamical motifs—such as distinct low-dimensional manifolds, transitions between attractor states, or mixed-selectivity representations—depending on the training sequence. In parallel, large-scale in vivo recordings (Neuropixels, two-photon imaging) allow us to test whether medial entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, and related circuits exhibit curriculum-dependent dynamics in behaving animals.

Alzheimer’s Disease: Circuit Computations and Disrupted Learning Algorithms

Alzheimer’s disease profoundly alters memory and navigation long before the most severe clinical symptoms appear. These behavioral changes reflect not only cellular and molecular pathology, but also disruptions in the underlying algorithms and representations that brain circuits use to learn from experience. Our goal is to use computational and systems neuroscience to reveal how Alzheimer’s disease disrupts the computations of entorhinal–hippocampal circuits and how these disruptions drive the behavioral changes seen in the disorder. We then use these computational insights to design principled tests of the synaptic and circuit mechanisms responsible for these failures.

To pursue this goal, we focus on behavioral paradigms that reveal how animals acquire, represent, and update information about space, time, and latent task structure—domains that show early vulnerability in Alzheimer’s models. By measuring how strategies, learning trajectories, and generalization patterns change in disease, we can identify which components of the underlying computations fail first.